Should I say Mass in an Empty Church?

What does it mean if I celebrate the Holy Eucharist in an empty church?

It depends on who you ask. For some, it means, or could mean, I am exercising a unique clerical privilege at the expense of solidarity with not only those under my cure who are sheltered-in-place, but also those around the world who are denied regular access to the sacraments.

For others, it means I am responding to my responsibility and duty to offer the Holy Eucharist, as the Sacrament of Christ’s Death, for the life of my parish, and for the life of the world.

These two positions seem worlds apart. I claim the position of the latter, and less popular one, at least in the United States. I understand (at least I think I do) the position of the first, but I do not recognize it as remotely representing my motives, theology, and practice. My aim here is to present the theological rationale as to why I say mass in an empty church. Not only that, but I hope to argue why we should.

It seems that at the heart of the divide are at least three questions: 1) what is the difference, if any, between clergy and laity, 2) what does solidarity mean, and the most important 3) is the Holy Eucharist a sacrifice?

What is the difference between clergy and laity?

I do not, for one minute, believe my ordination makes me better than someone who is not ordained. I believe my ordination has set me apart for a specific role in Christ’s Body, and I believe I have been set apart, not above, for this role as long as I am alive. If those in the ordained state, not caste, are guilty of suggesting or perpetuating the notion that our authority and responsibility elevates rather than humbles, we must repent.

In the ordinal of the 1979 Book of Common Prayer, the ordinand is reminded at the beginning of the examination that “the Church is the family of God, the body of Christ, and the temple of the Holy Spirit,” and that “all baptized people are called to make Christ known as Savior and Lord.”

St Paul speaks of the Body of Christ; a body that has diverse members that function for the whole. The eye does not see on behalf of the eye, but on behalf of the whole body. The hand does not open for the sake of the hand, but for the whole body. The parts do not exist independently of the others. Yet, if the eye were removed, the body could not see. If the ear were removed, the body could not hear. “Now you are the body of Christ and individually members of it. And God has appointed in the church first apostles, second prophets, third teachers…” He then asks, “Are all apostles? Are all prophets? Are all teachers?” (1 Cor. 12) The answer is no. We should not forget these words directly precede his famous exhortation on love.

The priesthood, like the laity, is an organ of the body. It does not function for itself, but for the whole body. The priestly organ is not granted greater value, but a specific function. As organs, to quote Fr. Robert Moberly, they do not confer life on their own, “working organically for the whole Body, specifically representative for specific purposes and processes of the power of the life, which is the life of the whole body, not the life of some of its organs” (Ministerial Priesthood, pg. 68). The result of eliminating the roles between clergy and laity would result in not in greater unity, but disunity. Instead of feet and hands and eyes, there would only be elbows. The effect would be defect.

Baptism is a kind of ordination into the priesthood of Jesus Christ. We are all called to offer ourselves (a priestly action) to God: “And here we offer and present unto thee, our selves, our souls, and bodies, to be a reasonable, holy, and living sacrifice unto thee.” The ministerial priesthood does not compete with the priesthood of all believers. Both are participations in Christ’s Priesthood.

This is a long quote, but one worth reading, by Henry Liddon:

“The Christian layman of early days was thus, in his inmost life, penetrated through and through by the sacerdotal idea, spiritualized and transfigured as it was by the Gospel. Hence it was no difficulty to him that this idea should have its public representatives in the body of the Church, or that certain reserved duties should be discharged by Divine appointment, but on behalf of the whole body, by these representatives. The priestly institute in the public Christian body was the natural extension of the priesthood which the lay Christian exercised within himself; and the secret life of the conscience was in harmony with the outward organization of the Church…Where there is no recognition of the priesthood of every Christian soul, the sense of an unintelligible mysticism, if not of an unbearable imposture, will be provoked when spiritual powers are claimed for the benefit of the whole body by the serving officers of the Christian Church. But if this can be changed; if the temple of the layman’s soul can be again made a scene of spiritual worship, he will no longer fear lest the ministerial order should confiscate individual liberty. The one priesthood will be felt to be the natural extension and correlative of the other” (University Sermons).

It is a real abuse of clericalism to suggest that we all must be the same in our function in the Body of Christ.

What is solidarity?

What, therefore, does it mean to be in Eucharistic Solidarity? Among the more puzzling responses during the pandemic has been the suggestion that, since the laity are not allowed to receive the Holy Eucharist, priests should not as well. Furthermore, since Christians around the world are unable to have regular access to the sacraments, demanding such access is an act of Western Privilege.

If there were no divinely appointed functions within the Body of Christ, I would agree. I also understand, and appreciate, the pastoral impetus in the above statements. When one part of the Body grieves, as St Paul reminds us, we all grieve. And we should. We must. I do not, however, think that grief, solidarity, and the priestly function need to be exclusive of one another.

If the people cannot receive the Holy Eucharist, I argue it is even more important that the priests offer the sacrifice for them. To not stand at the altar, representing them and their prayers and sufferings, in union with Christ’s Sacrifice would be an act of greater privilege, in the sense that privilege means ‘private law’ unto myself. While so many are isolated and many are forgotten in the world, they are remembered at the altar. I’m certain priests who are saying mass daily (or weekly) are still receiving requests for prayer. It’s not because they have a special line to the Almighty or that their holiness will deliver petitions with greater clarity. It’s because they can take those petitions to the altar to be joined with Christ’s offering to the Father. Again, I argue that we are greater solidarity at the altar than at home. Never have I said mass in a nearly empty church and felt good about it. It’s always difficult. And that’s why I need to be there.

Is the Holy Eucharist a Sacrifice?

If the answer to this question is no, then it makes absolutely no sense to say mass in an empty church. I would even go further and say, if the answer is no, the mass makes no sense. This question, I believe, is at the heart of the first two asked in this offering. For if the Holy Eucharist is a sacrifice, independent of the reception of Holy Communion, then the role of the priest is clear and the question of solidarity is answered. Perhaps the reason why there’s so much diversity in opinion is because this most important aspect of the Holy Eucharist is also the most neglected.

The Prayer Book clearly acknowledges that the Holy Eucharist is a sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving, but it is also much more. Rather than re-sacrificing Jesus Christ, an accusation made during the Reformation, the mass re-presents the one sacrifice once offered. The Holy Eucharist places us at the foot of the cross with the Blessed Virgin Mary and St John, but even more, we are given the great gift of uniting our prayers with the one sacrificial act that was ever efficacious before the Father.

Prayer B in the 1979 Book of Common Prayer, “Unite us to your Son in his sacrifice, that we may be acceptable through him, being sanctified by the Holy Spirit.” The action of the Holy Eucharist is still complete even if the laity do not receive Holy Communion. Is Holy Communion ideal? Of course it is, assuming they are properly prepared. Let us remember that the Prayer Book neither assumes nor suggests that everyone should take communion. The climax of the Eucharistic action is the presentation of Christ’s separated Body and Blood under the forms of bread and wine. His sacrifice is given to us so that we may offer the same to the Father.

This justifies saying mass without communion. The presentation of the Crucified Lord, sacramentally, also justifies spiritual communion. What are the ‘benefits of Communion’ as stated in the Prayer Book? The catechism teaches it is the forgiveness of our sins, the strengthening of our union with Christ and one another, and the foretaste of the heavenly banquet. These benefits come when we come in contact with the sacrifice of the cross, made present to us in the Eucharistic Sacrifice.

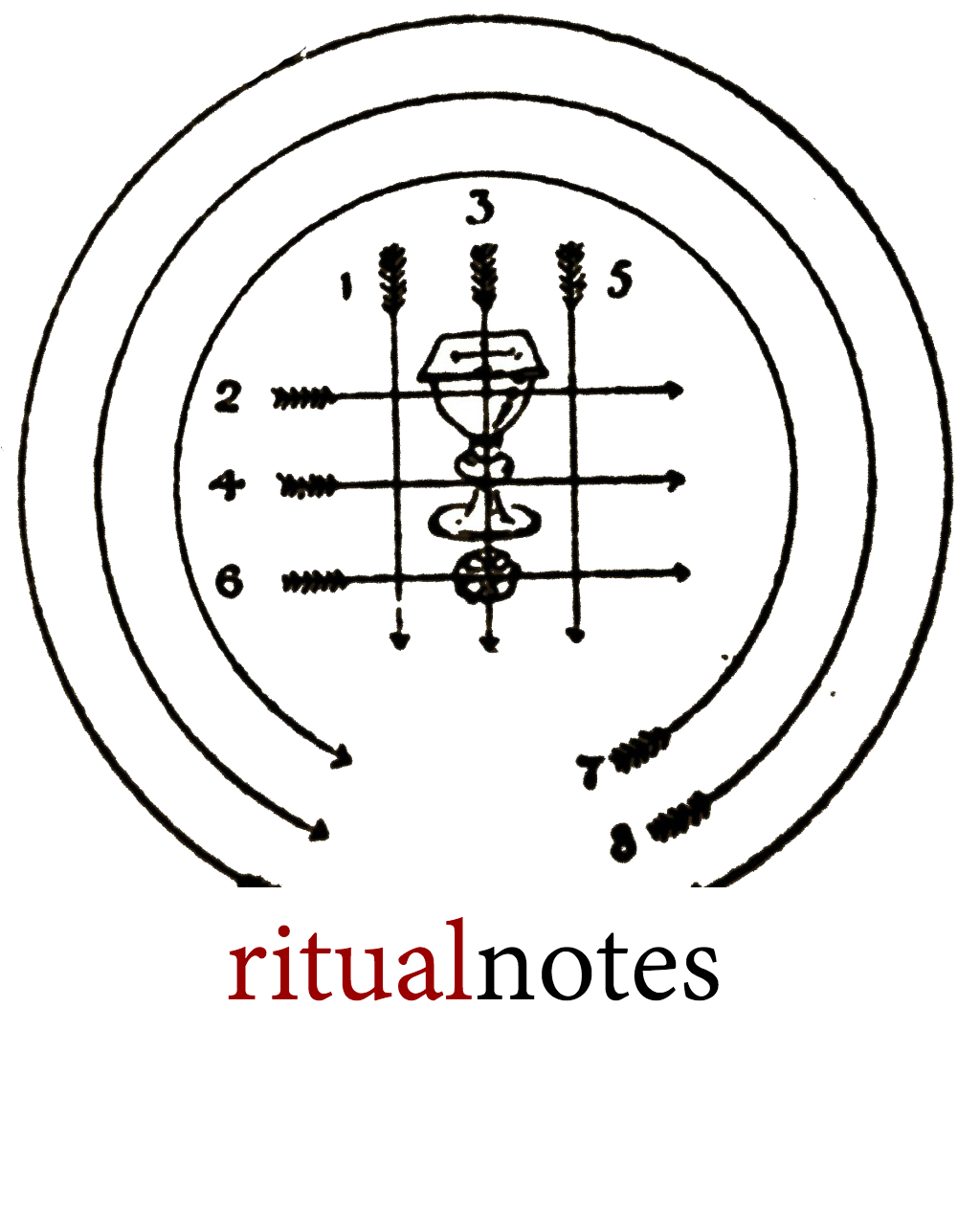

This is not done easily via YouTube. You’ll receive no argument from me. What worries me more about livestreaming is not that it’s online, but that it can be accessed on demand. At least with St Charles Borromeo erected pillars to let people know where masses were said (and I presume bells were rung) they could look at their windows and unite themselves to the mass offered in solidarity with their isolation. Once upon time, a priest could ring the bells during mass, and all in the village, whether working the fields or inside their home, could stop and kneel in prayer in union with the Sacrifice. If I ring my church bells, it’s barely heard outside the parking lot. Watching the mass later is perhaps a re-presentation of the re-presentation. I’m not sure what all that means.

Yet I am more worried about the results if I stop saying the mass and stop streaming, whatever form that might be. If priests shift from offering sacrifice, then what is the function of the priest? Have we shut off an important organ to the Body? If priests stop offering the sacrifice (the priestly function and responsibility), will the church abandon her priestly character, as a participation in Christ’s Priesthood? I don’t have any good answers. But, if I’m not at the altar, where will I be? I can’t be in the hospital, I’m not allowed in the soup kitchen, and it’s too dangerous to sit at someone’s kitchen table. Where’s the one place where all these places intersect?

I will go the altar of God.