Last Rites

He died as I said, “Depart O Christian soul, out of this world.” That’s never before happened to me and it was a parting gift from this lovely, devout man.

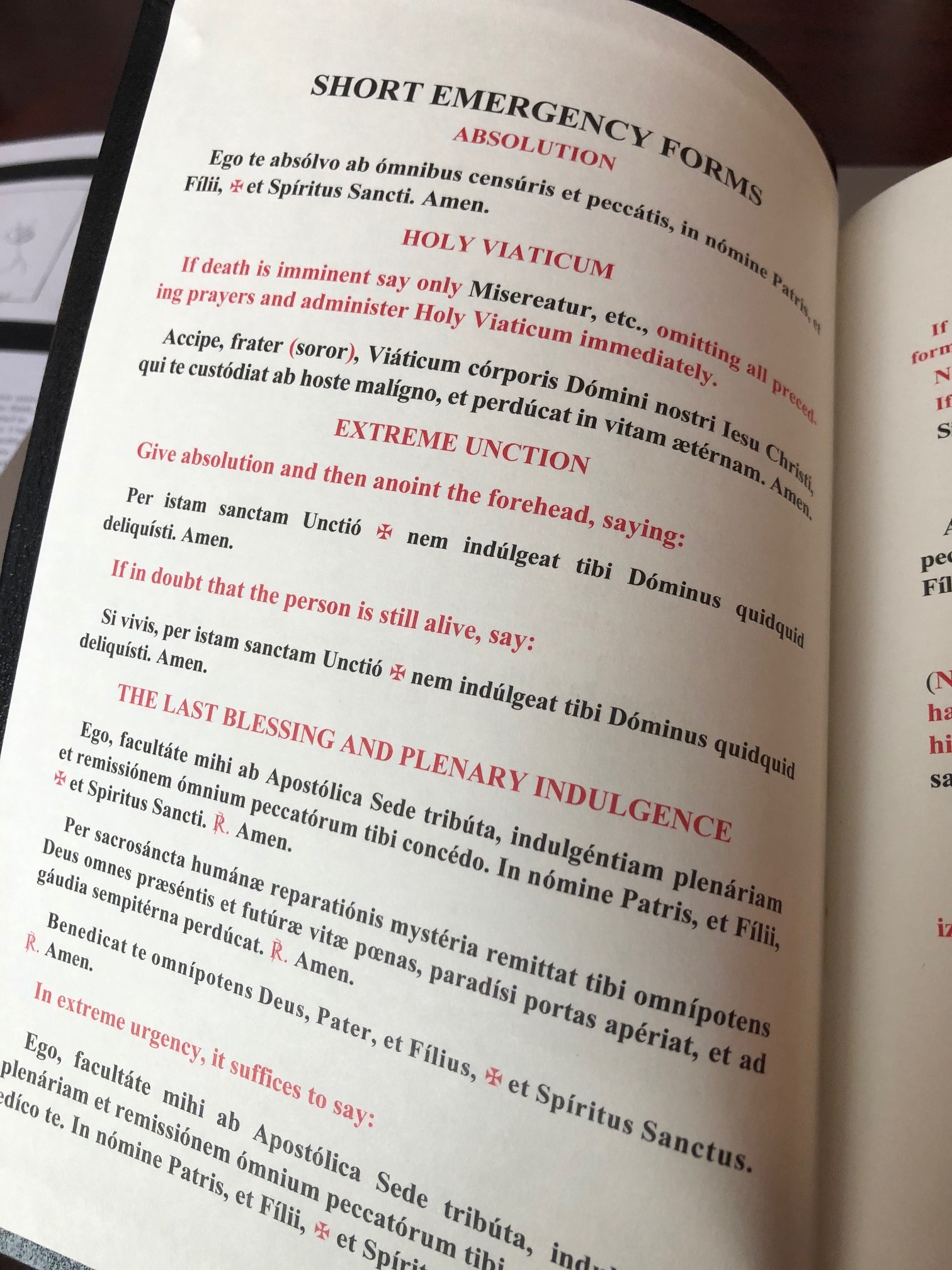

People are curious, but are nervous to ask what happens, at least as the Church is concerned, when we die. Families know to call the priest but are often unsure what they are calling us to do. Confession, unction, and Holy Communion (viaticum) constitute the “last rites” of the Church: sacramental strength before our soul is separated from our bodies in death. Very often, at least in my experience, it is not possible to administer all three. In the majority of cases, the dying person is asleep or not communicative, making confession impossible and/or they are unable to eat, making reception of the Holy Communion impossible, leaving only the final anointing with the oil of the infirm (extreme unction).

Ideally the room is to be prepared with candles, holy water, and a crucifix. Again, most of the time such preparations are not possible due to time and other considerations. I keep a violet stole in my car and I used to keep a small crucifix as well. That crucifix is now buried with a man who kept it and held it constantly after I anointed him before his death last year. Yesterday, when I received the call that this servant of God was declining faster than anticipated, I took a crucifix down off the wall, grabbed the oil, cotta, and stole and quickly went to him.

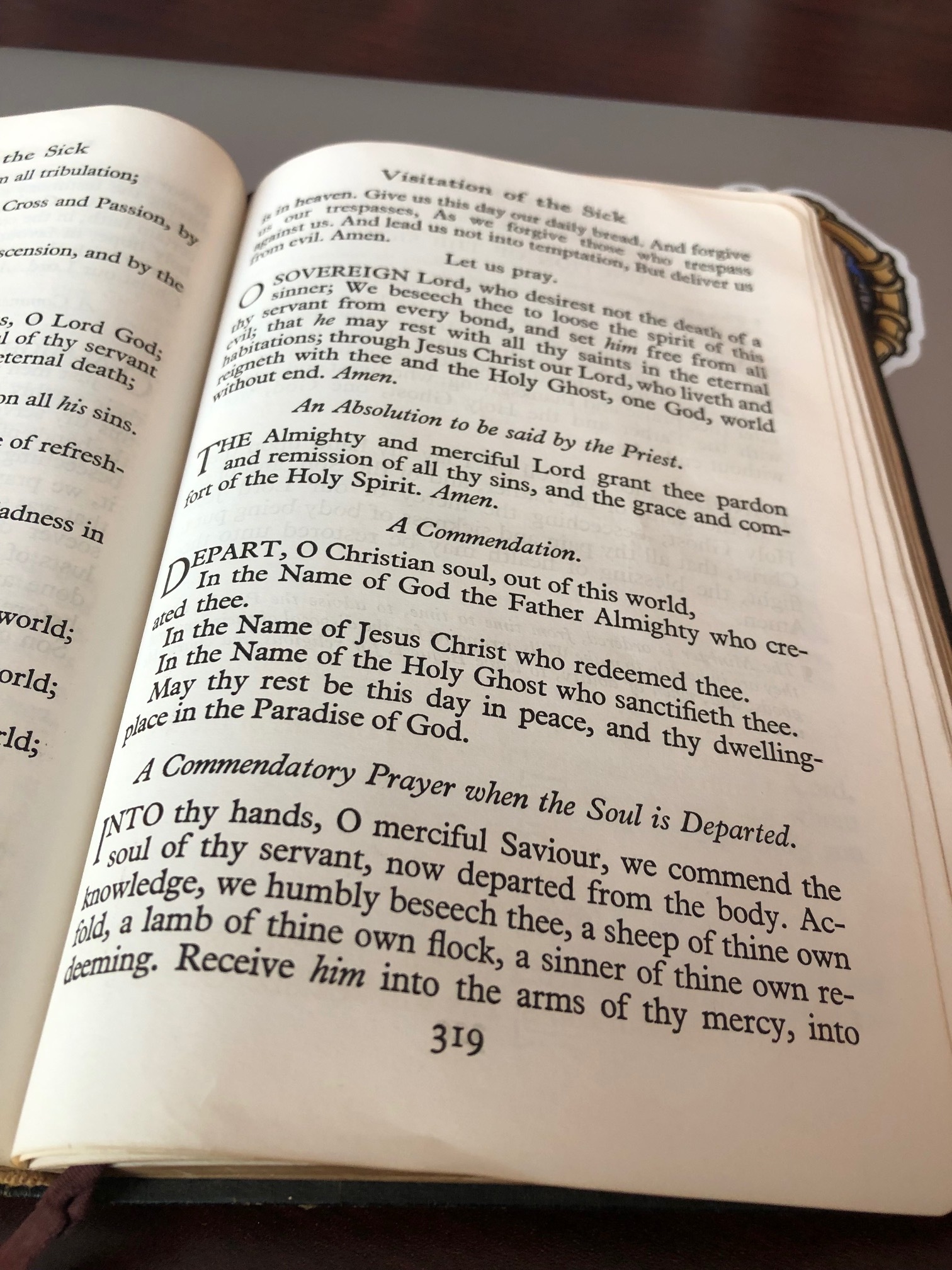

As there is no liturgy called “Last Rites,” the priest must make decisions. The 1979 Book of Common Prayer has liturgies for Reconciliation of a Penitent (confession), Ministration to the Sick (anointing), and Communion Under Special Circumstances (viaticum). A similar arrangement is found in the traditional Roman Ritual. While the 1979 Book of Common Prayer has traditional prayers for the dying (taken from the 1928 Book of Common Prayer, which I should add, also includes absolution), the prayer for anointing in the face of death is wanting. The prescribed words that accompany anointing do not mention the forgiveness of sins but rather state that the person is anointed with oil in the Name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The optional prayer that follows is wonderful in cases where there is hope for recovery, but not necessarily in the face of impending death. While the line “restore you to wholeness and strength” certainly implies spiritual wholeness and strength, in the case of a dying person I prefer the traditional formula for anointing, “By this holy anointing may the Lord forgive you all the evil you have done." [Of note, the Church of England removed “restore to wholeness and strength” in Common Worship’s Ministry with the Dying, a prudent move.]

The translator’s preface to the 1964 Roman Ritual acknowledges that the rites assume ideal circumstances and while acknowledging that ideal circumstances are often just ‘ideal,’ the preface chastises priests for not doing their part in keeping the fullness of the rite. I think there is real merit to the knuckle slap. It’s not too much effort to put on the cassock, cotta, and violet stole and it’s not too much effort to bring a crucifix, even in situations requiring immediate attention.

In yesterday’s case, as his breathing was very shallow, I knew I didn’t have time for the full traditional rite but I did place my wall crucifix on his chest, put on cotta and stole, and immediately anointed him with the traditional words. Confession and Communion were not possible. In placing the crucifix before them, I ask the person to unite their sufferings to that of the Crucified Lord and call on the Name of Jesus in their hearts. This is very likely the context for Julian of Norwich’s Revelations as she gazed upon the crucifix as she received the ministrations of the Church in her illness.

The Litany for the Dying followed the anointing. It is powerful and sobering and it is good for the family to join the petitions. The Litany follows the structure of the Great Litany and concludes with the Agnus Dei, Kyrie, Our Father, and Collect. It was after the collect asking for God’s deliverance from evil that I again touched the forehead of this servant and made the sign of the cross. His breaths had been far apart but his head was warm.

“Depart, O Christian soul, out of this world;

In the Name of God the Father Almighty who created you;

In the Name of Jesus Christ who redeemed you;

In the Name of the Holy Spirit who sanctifies you.

May your rest be this day in peace, and your dwelling place in the Paradise of God.”

I finished with the prayer of commendation and we noticed his color had changed. The breathing had stopped. He obeyed the command and gave up his spirit. It was finished.

As the Church calls is, a happy death.