Lex Agendi

If you want to alter a person, put them near an altar.

If you want to alter a place, place an altar.

I’m convinced of this.

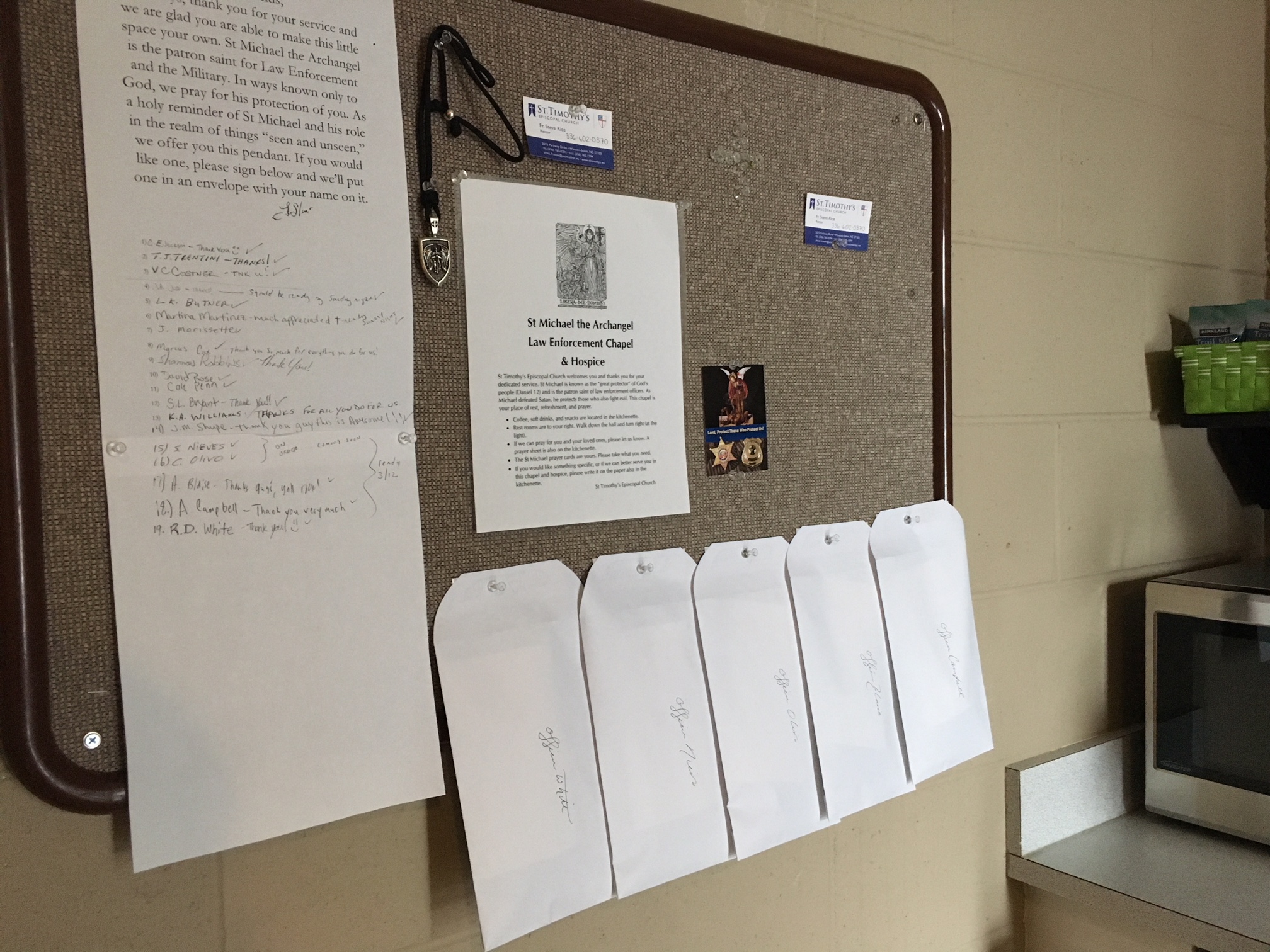

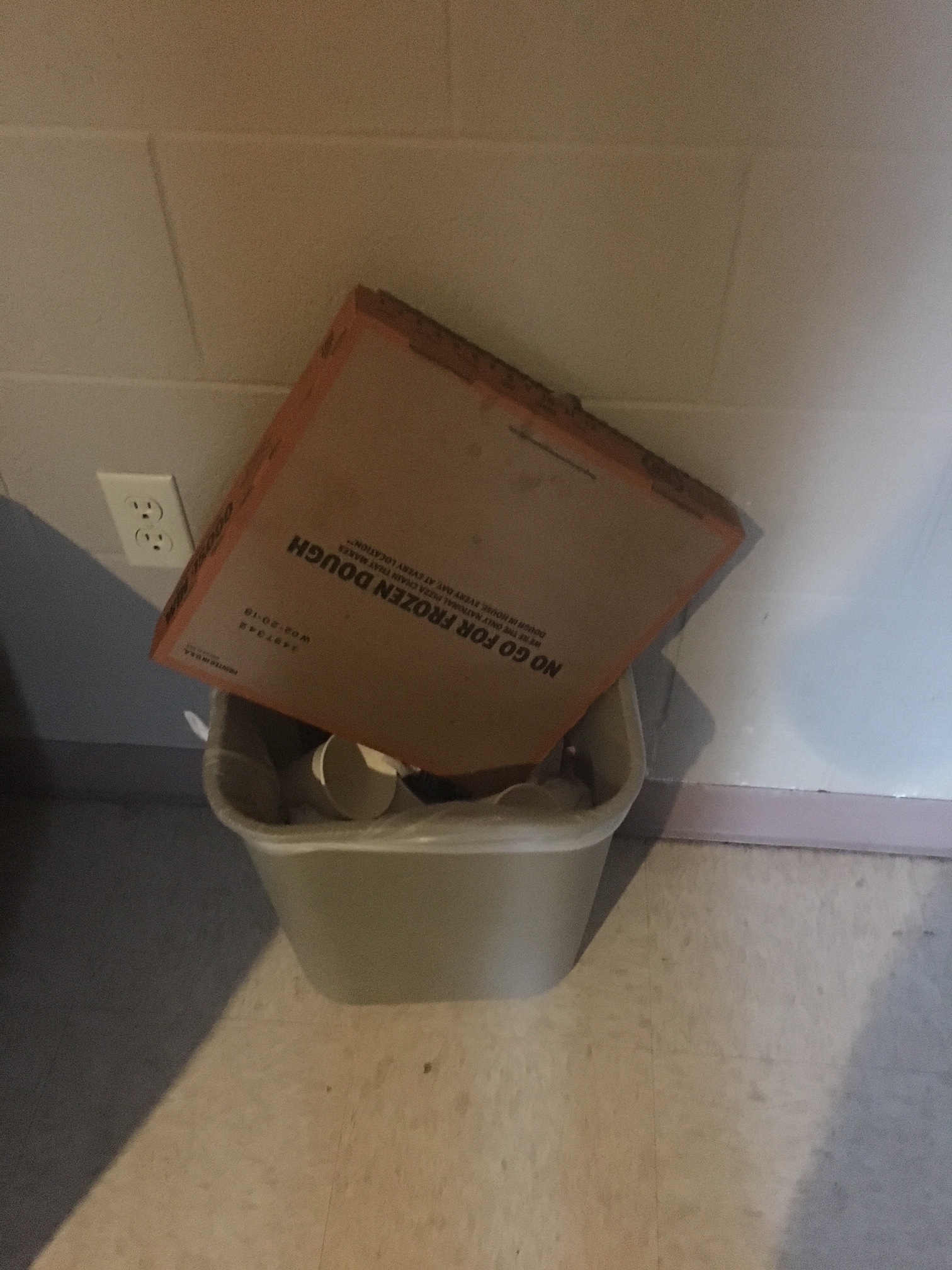

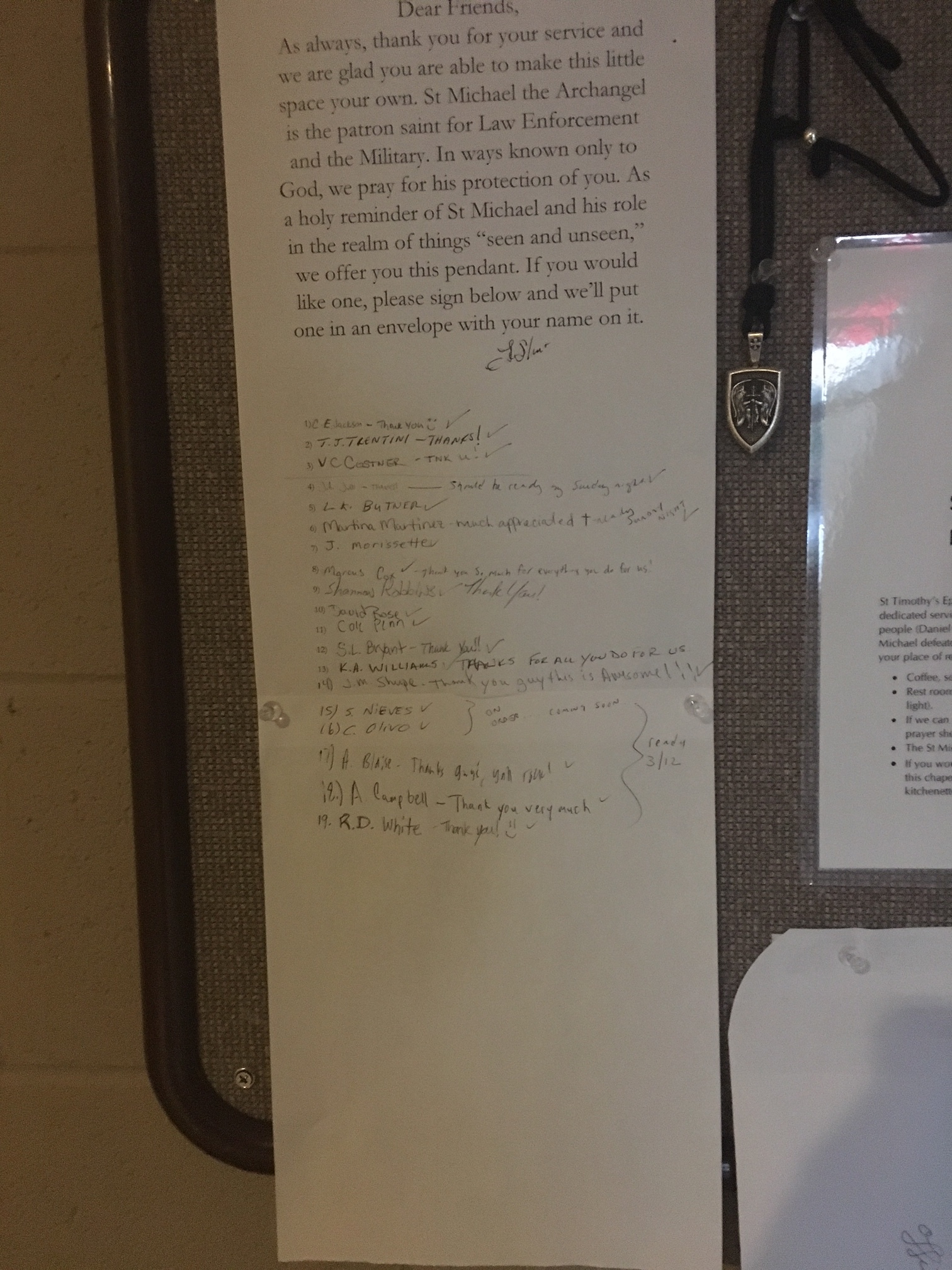

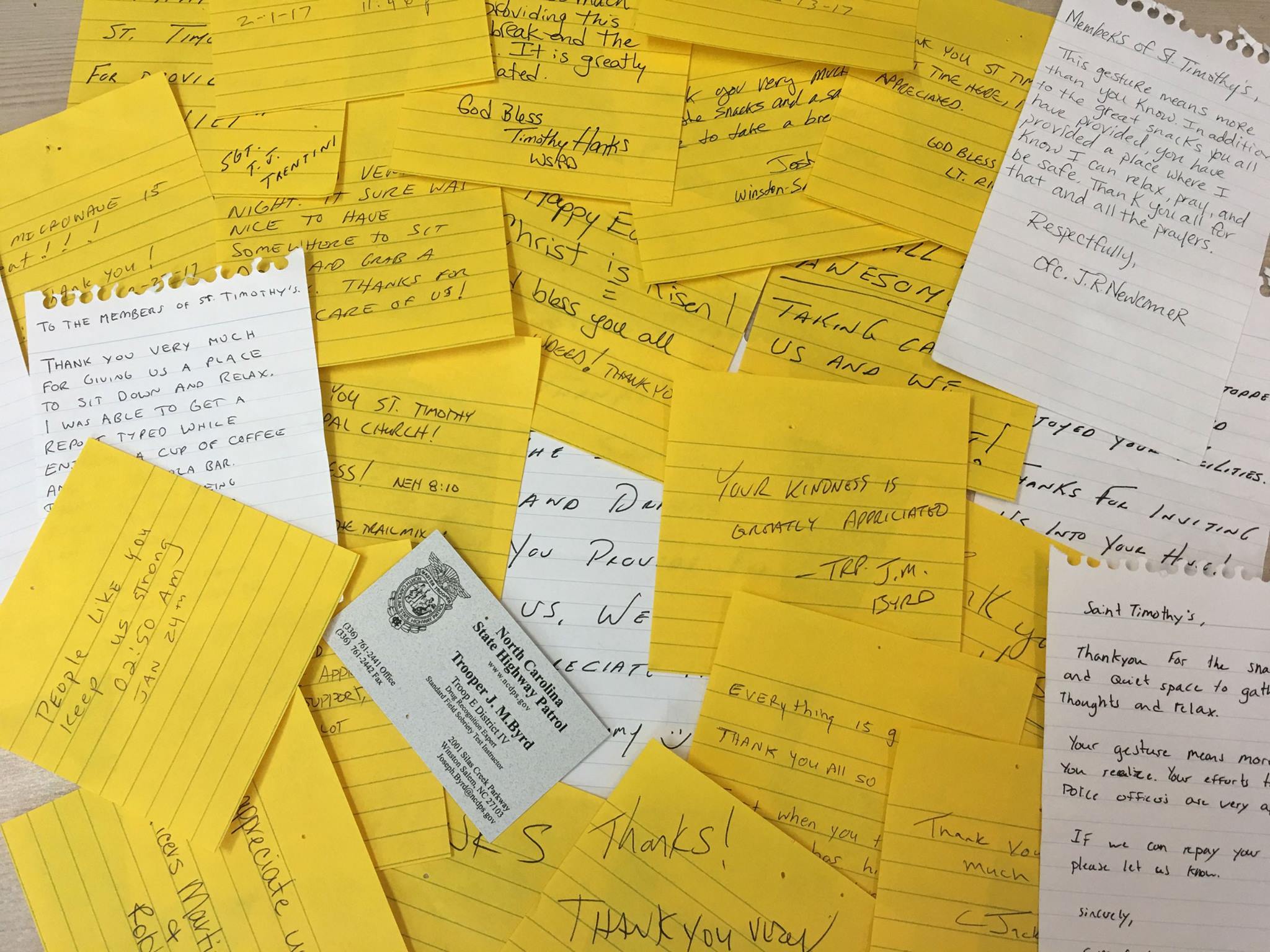

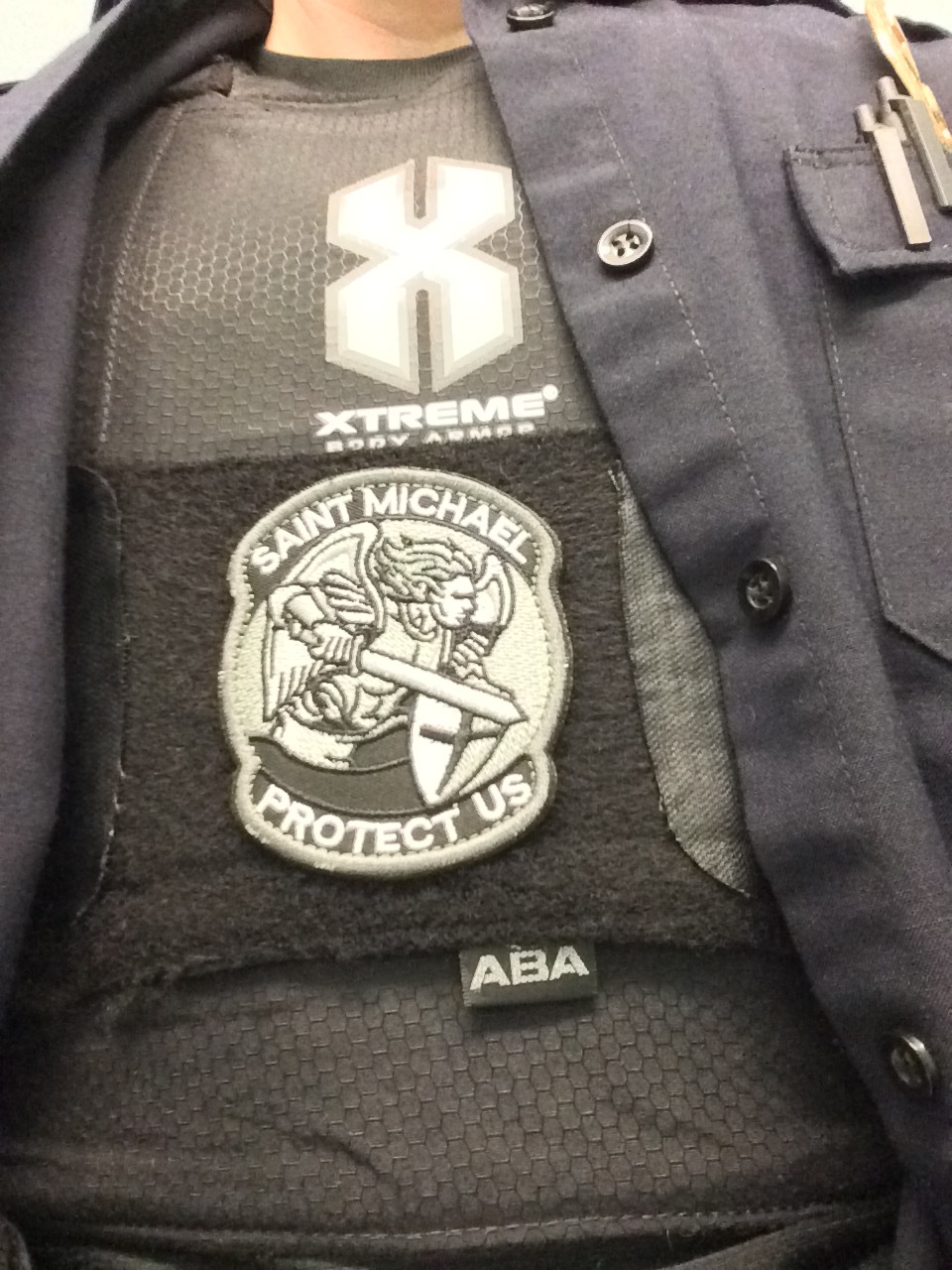

This morning on my way to the priests’ sacristy, I noticed a pizza box in a trashcan that was left overnight. Apparently pizza was on the menu for midnight lunch. I looked on the bulletin board above the empty pizza box. Two of the five packets I left the day before containing St Michael pendants have been taken by their new owners. The space was quiet at 7:30am, but I knew it was full just a few hours earlier.

This is an almost daily routine for me. This is a large, but mostly nocturnal, ministry for our local law enforcement. They come to this church to rest, eat, write reports, and pray. I have no idea how many have the code to get in. I know that when we hosted a late-night barbeque in the late summer, some 50 officers arrived for a quick bite to eat before they went back to walk the thin blue line. I recently found a lovely pendant of St Michael and hung one of the bulletin board asking if anyone would like to have one. So far, 19 have taken me up on it. I know some of the officers personally now. We text and they leave notes, but by and large, they come when I am asleep. This is their midnight church.

This all happened by taking a poorly designed, underutilized space and praying in it. If we want to alter a place, place an altar. If we want to alter a person, put them near an altar.

All, all, of our works of mercy flow from a discipline of prayer (stay tuned for upcoming posts on the Society of St Joseph of Arimathea and the homeless shelter).

In all our efforts to stimulate change in people and places, we often forget that the fount of justice is prayer. In all our efforts to revitalize the church and promote engagement and growth, we often forget that prayer is the transformative agent. And in all our efforts to engage the world by moving away from the church building, we often forget that sanctuary requires space.

Episcopalians love to quote the fifth century axiom from St Prosper of Aquitaine, ut legem credendi lex statuat supplicandi (the law of praying establishes the law of believing), often reduced to lex orandi, lex credendi. Translated it means what and how we pray establishes what we believe. If you want to change someone’s theology, first change their worship. This, by the way, is why any Prayer Book revision is so very, very important.

But the rule of prayer addresses more than what we believe. If I may be so bold, I would also add to lex ordandi, lex agendi. The rule of prayer establishes the rule of acting. Richard Hooker, who like St Prosper is quoted but never read, followed the thinking St Thomas Aquinas by placing religion within the virtuous realm of justice, or more accurately, justice flows from religion. “So natural is the union with Religion and Justice,” Hooker writes, “that we may boldly deem there is neither, where both are not.” Justice is to give someone what is their due. Religion is the highest form of justice in that it gives God his due.

If we wish to seek justice, we should begin with prayer. For it is in prayer (religion) that we are illumined by the truth of the dignity of the human person as created in the image and likeness of God and it is this illumination that shines light on our complicity in injustice and lights the path for mercy.

If you want to alter a person, put them near an altar.

If you want to alter a place, place an altar.